Spanish

Terminology

There is a rather intense debate when it comes to terminology. While I tried to provide the least-biased summary possible, recognize that others have different interpretations. I also realize that saying “comes from” is vague, but that is because most of these terms have to deal with identity rather than necessarily geographical origin.

Read More:

https://www.exploratorium.edu/sites/default/files/Genial_2017_Terms_of_Usage.pdf

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-11-22-me-59558-story.html

Spanish (People)

Just like how an English person is someone from England, a Spanish person is someone from Spain.

Hispanic

This refers to someone who speaks Spanish or comes from a Spanish-speaking culture. The result is that this does not include Brazil nor does it include those living in primarily Spanish-speaking countries who speak an Indigenous language or identify as Indigenous. Many reject this term from its ties to colonialism.

Chicane/Chicanx/Chican@/ Chicana/o/Chicano

Chicane refers to an individual with Mexican descent born and/or living in the United States. It is pronounced chee-cahn-ay.

See the Latine section for context on why different endings are used.

Latine/Latinx/Latin@/Latina/o/Latino

Latine (see below for what the different terms represent) refers to individuals with roots in Latin America (which includes Brazil, but excludes Spain/Portugal and primary English/French/Dutch speaking areas). However, many individuals prefer to identify by their country of origin (e.g. “I’m Colombian”) rather than using a broad term like Latine).

Spanish is a gendered language, which makes inclusive language difficult at times. In general, Latino refers to someone who identifies as male, and Latina refers to someone who identifies as female. However, when you have a group of people (unless they all identify as female), you default to using the male term. This creates a gender hierarchy and doesn’t leave much space for those who do not identify as either female or male.

Latino: Commonly used, but least inclusive

Latin@: The use of the @ symbol represents the term ending in an “a” or an “o,” but still views gender as a binary.

Latina/o: By putting the female ending before the male ending, this tries to counteract the gender hierarchy, but again is a binary term.

Latinx: The “x” is supposed to represent a variable, meaning it is open to any gender, however it is difficult to pronounce in Spanish. It tends to be used in academic writing in English. It is pronounced Latin-ex in English.

Latine: The goal of this term is to accomplish a similar goal as Latinx, but allow it to be more easily pronounced in Spanish. It is pronounced lah-teen-ay.

These videos provide nuance and some real perspectives, but don’t necessarily all agree. Note that in the second video, an expletive is used around 7 minutes, although it is bleeped out.

Race v.s. Ethnicity

This is a complicated matter that often leads to a lot of individuals being confused when filling out demographic-collecting documents. Those in the US that are counted as Hispanic have self-identified as that in the census or on other documents.

“In the eyes of the Census Bureau, Hispanics can be of any race, any ancestry or any country of origin.”

“According to the Census Bureau, Hispanic origin and race are two different concepts, and everyone should answer both questions even though many Latinos consider their Hispanic background to be their “race.” The Census Bureau says being Latino is an ethnicity, not a race.”

The census identifies four races: White, Black, American Indian or Alaska Native, or Asian or Pacific Islander. You can also write in your own race or check multiple boxes. “Each of the race categories has the option to write-in more detail, for example, a person could mark Mexican as his Hispanic Origin, and White as his race. Or someone could mark Dominican as her Hispanic Origin, and Black as her race.”

Learn More:

Is being Hispanic a matter of race, ethnicity, or both? Pew Research: Who is Hispanic?

Census Will Ask White People More About Their Ethnicities 2020 Census: Hispanic Origin

Listen: Latinos Are a Huge, Diverse Group. Why Are They Lumped Together?

Size and Distribution

Population data demonstrates that we have not taken in any Central American refugees in the past 20 years, but this does not mean there are not people of Central American descent that immigrated/moved/were born here. Many of these individuals speak Spanish, but many do not, and being from a Latin American country does not mean someone speaks Spanish. Latin American Indigenous languages bare almost no resemblance to Spanish. It is also important to note that being Hispanic/Latine does not make someone a Spanish speaker and being a Spanish speaker does not mean someone is Hispanic/Latine. However, because Hispanic/Latine identifying individuals overwhelmingly are Spanish speakers or have contact with the language, this data will be used.

Wisconsin Hispanic or Latino Origin Population Percentage by County

The Hispanic/Latine population is principally concentrated in Southeastern Wisconsin near Milwaukee, Northeastern Wisconsin near Green Bay, and West-Central Wisconsin near Arcadia.

The growth of the Latine population in rural areas is an important trend, especially for schools (see Arcadia below). This growth can be vitally important for districts with small/declining enrollment, but it also means that there often are adjustments and additions they need to make in terms of staff, coursework, and support services.

The graph labels are important to note here, as it starts at 75% white, but it is still clear that the Hispanic/Latine population is growing. 2019 data shows the state is nearly 7% Hispanic/Latine.

Image Source: https://cdn.apl.wisc.edu/publications/Wisconsin_Demographics_RERIC_2018.pdf

Though this data is from 2010, it is mostly accurate compared to 2019 data. There has been about a 12% growth in the percent of Hispanics/Latines that are Central American.

Image Source: https://washington.extension.wisc.edu/files/2010/07/Latinos-in-Wisconsin-A-Statistical-Overview.pdf

About 1/3 of Wisconsin Hispanic/Latines are born outside the US, about 1/5 are born in a different state, and just under half are Wisconsin-born. The percent born in Wisconsin has been increasing. Additionally, the population in general tends to be younger than the overall Wisconsin population.

Source: https://washington.extension.wisc.edu/files/2010/07/Latinos-in-Wisconsin-A-Statistical-Overview.pdf

Language and Education

Spanish is offered at almost every high school in Wisconsin and in general is the first language a school will decide to offer. It is difficult to determine the amount of Spanish speakers in the state, but “Of the 462,381 people who reported speaking a language other than English at home, 243,560 (about 53%) speak Spanish.” [Source: Wisconsin’s Language Landscape]

This is dated data, but more recent estimates do show fairly consistent figures. As mentioned above, many Latine people do not speak Spanish. In fact, 1/3 of those in Wisconsin do not. There is a complex web of factors that contributes to this, and language “loss” is common among younger generations, especially when the schools they attend to not offer immersion/heritage courses.

Many people will say that newer linguistically-diverse populations are not learning English as fast as prior groups, and this is categorically false. However, I would argue this is not necessarily something that entirely deserves celebration, as mother tongues are being lost at the expense of the push to quickly learn English.

Once again, being a Latine student does not mean that you are Limited-English Proficient, but it is important to see that the districts with the highest concentrations of Latine students tend to be rural and are mostly distinct from the top 10 at left. Source: Source: https://washington.extension.wisc.edu/files/2010/07/Latinos-in-Wisconsin-A-Statistical-Overview.pdf

Spanish is overwhelmingly the language offered to and taken by Wisconsin students.

Source: Wisconsin Language Landscape

(Dual Language) Immersion Programming

Dual Language Immersion (DLI) is a special form of bilingual language education in which classes are half students who are dominant in the target language (e.g. Spanish) and half who are dominant in English (although there are some exceptions). Programs can be either 90/10, 90% of instruction in Spanish, 10% in English or 50/50 where it is equal for both. In some schools, they start off 90/10 and each year add a little more English. The goal is for students to support the linguistic development of one another. There is not one accurate database of bilingual programs in the state (from what I have found), so below is just a highlight of some programs. The School Spotlights tab also includes information on the majority of these programs!

Indigenous Central/South American Languages

Again, it is important to not group these languages in with Spanish. The only reason it is being included here rather than having its own dedicated page is because I do not feel that I have enough (accurate) information to provide a full overview. Please contact me if you can point me in the direction of resources. These languages are distinct from Spanish, but because students and families may come from countries where Spanish is the primary language spoken, the assumption often is that they speak Spanish. Watch the videos below to learn about how you can support these students and families.

Check out this article to learn more: Supporting Indigenous Latinx Students' Success in U.S. Schools

Leaders in Spanish/Bilingual Education

From the German education days of the 1800s to the fight for Spanish bilingual education in the mid 20th century, Wisconsin has long been a leader in language education. Spanish has been the primary focus as of the last half century, and there are some incredible leaders in the state who have paved the way for these programs, Tony Baéz one of them. Check out the interview with Mariana Castro as well as articles and videos linked in the resource section to learn more about this important work.

Learn Spanish Words and Phrases!

Hola — Hello

¿Cómo estás? — How are you?

¡Adiós! — Goodbye!

History

Latino Wisconsin is a fantastic new film documenting just what the title suggests. It is broken into 5 chapters, each about 10 minutes long.

Chapter 1 - On the Farm

Chapter 2 - In Rural Communities

Chapter 3 - Art, History, and Activism

Chapter 4 - In the Schools

Chapter 5 - Today and Tomorrow

Read More: https://milwaukeenns.org/2020/12/29/documentary-tells-the-story-of-latino-wisconsin/

The majority of the overview below will be based upon Mexicans in Wisconsin. There are Spanish speakers from other nations represented in the state, and articles and resources are included below, but there unfortunately is only a text for Mexicans (to my best knowledge). The histories of other Spanish-speaking groups are included throughout as much as possible! Additionally, see Dreamers of Wisconsin’s helpful explainer on Wisconsin’s Mexican and Central American Immigrant Communities.

Overview

“Census records show that few Spanish-speaking immigrants had settled in Wisconsin between 1850 and 1910. […]

Mexicans began arriving in large numbers after the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, and remained the dominant immigrant group until the 1950s when many Puerto Ricans began to settle in Wisconsin. More Mexicans arrived to work in Milwaukee factories in the 1920s but the Depression forced many to return to Mexico. The out-migration continued until the labor shortages of WWII caused a reversal. Mexican-American farm workers, mainly from Texas, also began to come back to rural Wisconsin farms.. Mexican migratory farm workers had first been recruited in the 1920s to work in sugar beet fields and continued to come in increasing numbers until the early 1970s.

The emergency farm labor program, established in 1943 by the federal government, led to the placement of several thousand agricultural workers, most from outside the United States, throughout the remainder of the decade. Wisconsin farmers participated in the Bracero program from 1951 to 1964, which brought workers from the southwestern U.S. to Wisconsin. Diverse and better-paying jobs in urban areas led more Mexican-Americans to settle in Milwaukee, Kenosha, Racine, and Waukesha in the 1970s.”

Image Source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM22900

Quoted Material: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS1791

Origins

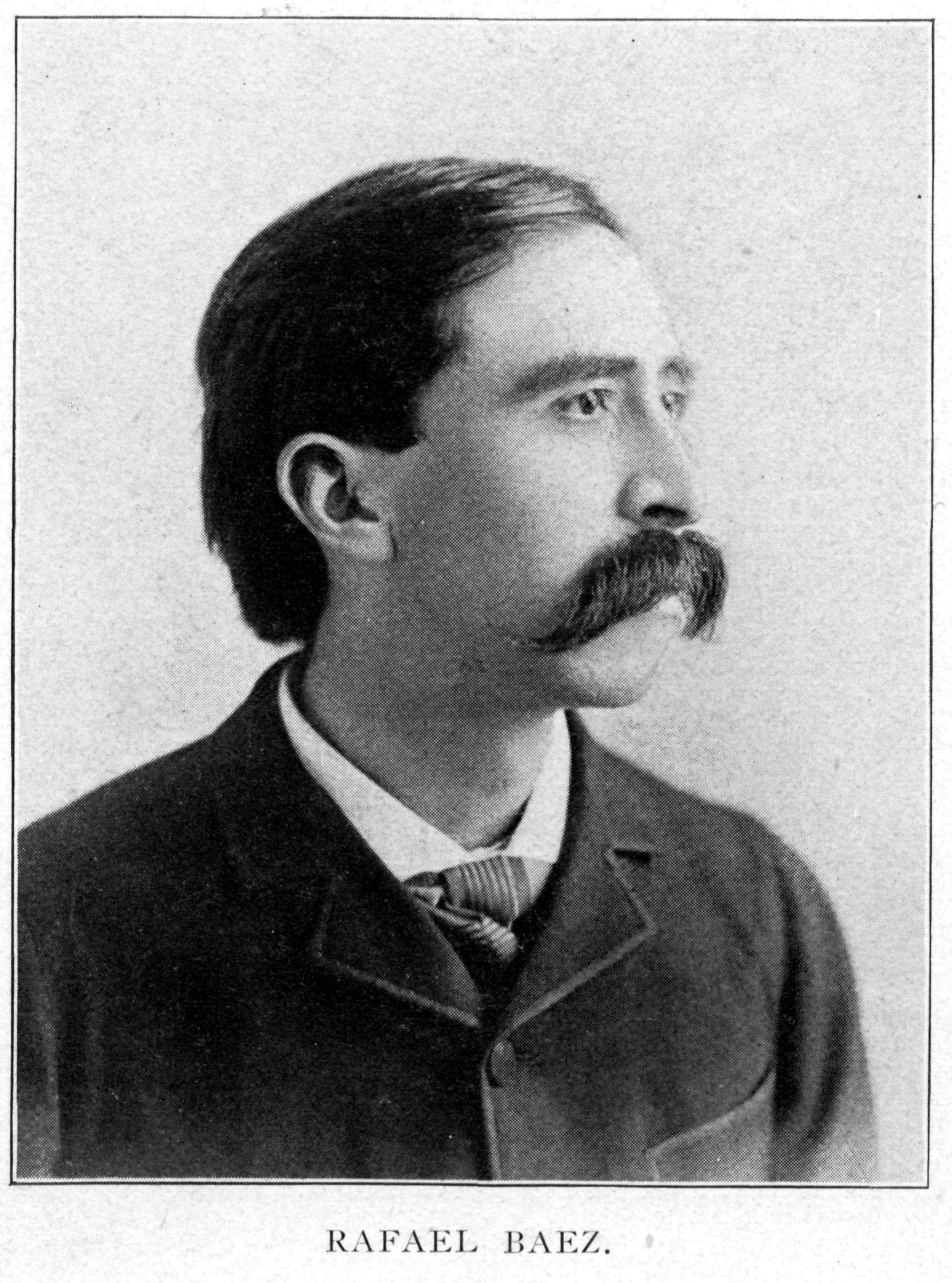

Raphael Baez, a musician, is widely recognized as the first Mexican (and Latine) to settle in Wisconsin. “Baez eventually settled in Milwaukee where he became a successful organist for a number of Milwaukee churches and then a professor of music at Marquette University. He was the school’s first Mexican professor and quickly became a respected teacher.”

Musician Raphael Baez One Of First Mexicans To Call Milwaukee Home

Image Source: https://www.mpl.org/blog/now/rafael-baez-the-first-latino-milwaukeean

Early Immigrants

The first two decades of the 20th century was mostly made up of “solteros,” single men that came on work contracts without family. The primary pull was agriculture or railroad work. Besides Milwaukee, most were in rural areas, and sugar beets were the primary crop being harvested (the workers referred to as betabeleros). The immigration acts/quotas of the 1920s did not put limits on the Mexican population, giving the farmers a cheap form of labor that they could hire for seasonal work. The Mexican Revolution more generally was a factor that led to US immigration.

Many Mexicans did come in with or obtain a higher education, but mostly due to racism, they were still blocked out of advancement outside of labor positions, resulting in many moving back to México.

In 1920, the first Mexican marriage was documented, a sign that people were beginning to settle down in the state permanently.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM44666

Religion

Religion was a source of unity, most identifying as Catholic or at least following Mexican Catholic practices. Religious groups in the state engaged in outreach with the Mexican community and tried in earnest to support the transition to the US. El Club Mexicano was established in Milwaukee to bring together Milwaukee Mexican Catholics.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM128190

Settling Down + Great Depression

Chain migration (a small group of individuals moving to one area spurs others following suit) led to a population increase. Early on, Waukesha was a community that had a large Mexican population. The reception of these immigrants wasn’t necessarily warm, but in the ‘20s and ‘30s, grocery stores and restaurants started opening up in these first communities, called los primeros. Similar to other immigrant groups, they created mutual aid organizations, mutualistas.

School was difficult for many children, teachers not extending the same linguistic support to Spanish-speaking students as they had done in the past for German, etc. Since the Mexicans arrived later, they didn’t have the same autonomy as earlier immigrant groups — they couldn’t necessarily “go rogue” and make their own schools to blatantly ignore rules.

Milwaukee’s Mexican population dipped below 1,500 during the Great Depression. Seen as surplus labor, they were always the first to be fired. The government would fund their return to México, mostly to avoid having to pay for welfare for them. These forced removals and deportations resulted in a great deal of family separation.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM91132

WW2 + Bracero Program + Post-War

During the war, many Mexicans served, and many others moved into wartime production industrial work (alternating with beet harvesting in the summer). Post war, their language skills started to become viewed as an asset, and businesses took advantage of these abilities to expand economies. The Mexican population began to climb up, and various groups, societies, and newspapers began to crop up, especially in the Milwaukee area.

The Bracero program brought in guest workers and lasted until 1964. Measures intended to protect the rights and safety of these workers were not followed, and work was hard. Door County’s cherry industry was especially supported by Bracero workers. Over-recruiting was a common practice, and this resulted in many being left jobless and wages being suppressed.

The canning business picked up as a result of the war, and as more moved into city jobs, rural agriculture jobs started to become desperate for employees. The focus turned towards domestic workers, Tejanos, those form Texas, making up the bulk of this new recruitment. Wautoma, Oconto, Rosendale, Lomira, and Fox Lake had large worker concentrations. Children of farm laborers often did not attend school, instead helping with the harvest. Those that did still continued to experience difficulties, bilingual assistance scant. There were some schools established near the migrant camps. The government ran official studies of migrant working conditions that highlighted how dependent the state was on these workers and how poor conditions were.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM92042

Education

It was often really hard for educators to work with migrant students because they didn’t have stability for education and were often 5+ years behind, of no fault to their own. The Governor’s Committee on Migratory Labor thought of different ideas to address the issue, summer programming, day care, church-funded schools, and specialized programs all being suggested. Wautoma in 1962 opened the state’s first Spanish Head Start program. That same year a daycare was opened for migrant children.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM128226

Jesús Salas + Obreros Unidos

“Milwaukee’s Latino population was mostly Mexican but included Puerto Ricans and other South and Central Americans. Therefore, in the 1960s through the 1970s social movement activists were careful to take a pan-Latino approach. In the 1960s, Mexican American migrants from Texas formed Obreros Unidos (United Workers) to organize migrant workers in Wisconsin’s agricultural fields and canneries.” In 1966, they marched from Wautoma to Madison to demand better conditions. “Inspired by César E. Chávez, they began organizing workers in Texas and followed the workers to Wisconsin. In 1968, Jesus Salas, a founding member of Obreros Unidos (OU) , the Wisconsin-based farm workers union, [and an educator] moved to Milwaukee to take a job with the United Migrant Opportunities Services (UMOS) and to organize the grape boycott in support of César Chávez’s union in California.”

Learn more about Puerto Ricans in Wisconsin

Quote Source: https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/mexicans/

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM92472

Transition to City Life

The threat of automation in the 70s pushed workers into city jobs. Groups like UMOS worked to ease this transition. During this time, the Milwaukee Latine population grew beyond Mexicans and Tejanos to include Cubans and more Puerto Ricans. Gil Marrero, Puerto Rican baseball player, came to Milwaukee to work with Latine youth. Centro Hispano opened in the late 60s.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM139263

Push for Bilingual Education + Higher Education Representation

The Mexican American Political and Educational Committee (MAPEC) along with other organizers (Puerto Rican Tony Baéz, mentioned above, an important figure) fought for bilingual education in Milwaukee schools. They fought for maintenance bilingual programs that would preserve and develop Spanish, rather than transitional ones that solely focused on rapid English acquisition, often at the expense of Spanish. They received funding to start bilingual education programs in several of the MPS schools.

“On September 16 and 23 of 1971, Latino students walked out of their Milwaukee Public School (MPS) buildings. They protested MPS’ lack of a bilingual education program, lack of curriculum that included Latino history, and lack of Latino teachers, as well as racist suspensions.”

Salas worked with UW-Madison students to push for the creation of a Chicane studies department. “…pan-Latino activism led to demonstrations calling attention to the small number of Latinos attending college. Mexican and Puerto Rican activists formed the Council for the Education of Latin Americans (CELA), which in August of 1970 led about 200 Mexican Americans and Puerto Ricans to sit-in in the UW-Milwaukee chancellor’s office demanding the university recruit more students from the Latino community and offer college courses on Latino culture and history. The protest led to UWM creating the Spanish Speaking Outreach Institute (SSOI) to better recruit and advise Latino students. Mexicans joined with Puerto Rican activists in the creation of La Guardia, a bilingual community newspaper.”

The Struggle for Bilingual Education

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM142267

1980s Immigration and Political Activism

Unemployment and economic crises in México led to an increase in immigration. Wisconsin was appealing due to its industrial and agricultural work. Immigration raids were common and though most Latines in Wisconsin were Wisconsin-born, the media attention focused on those that were undocumented.

While the Latine community was politically active, they weren’t always able to translate this work into tangible changes or political seats. This is not to say that there weren’t major victories.

Image source: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM142264

Present

There are two clear trends at present: 1) More Central American individuals are coming into Wisconsin, in alignment with a national increase. 2) Latines are growing in rural areas. The rural growth is especially important for schools, as mentioned above. The graph shown at right is for the Arcadia School District, but this general pattern shows up in many rural schools across the state. Be sure to watch the segment on Arcadia in the Latino Wisconsin documentary above.

Learn about Diego Román’s upcoming project: Teaching Local Socio-Scientific Issues to Latinx English Learners

Sources and Further Reading

Jesús Salas: A Lifetime Advocating for Migrant Workers' Rights in Wisconsin

Wisconsin Academy — Jesús Salas

Hispanic Heritage Month — Jesús Salas

Milwaukee Memory Project- Jesús Salas Oral History

Intercultural Exchange hosts speaker Jesús Salas

Jesús Salas: A Lifetime Advocate for Migrant Workers

WISCONSIN’S DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGES: IMPACT ON RURAL SCHOOLS AND COMMUNITIES

On The Census, Who Checks 'Hispanic,' Who Checks 'White,' And Why

SERIES: CHALLENGES TO WISCONSIN'S RURAL SCHOOLS

LACIS — Resources for K-12 Teachers and Students

Mexicans In Wisconsin: Sergio Gonzalez Aims To Set Record Straight

The Struggle for Bilingual Education

Report on the Status of Bilingual-Bicultural Education Programs in Wisconsin

Immigrant dairy workers transform a rural Wisconsin community