Ojibwe

Ojibwe is a language within the Agonquian family of languages. In Wisconsin, the tribes that speak it are: Red Cliff, St. Croix, Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, Lac du Flambeau, and Sokaogan (Mole Lake). These six tribes are known as the Lake Superior Chippewa Ojibwe. Ojibwe refers to both a language and a group of people.

Ojibwe speakers are concentrated in the northern portion of the state.

Terminology

Chippewa vs Ojibwe vs Ojibwa vs Ojibway

“There is no difference. All these different spellings refer to the same people. In the United States more people use 'Chippewa,' and in Canada more people use 'Ojibway,' but all four of these spellings are common. Since the Ojibwe language did not originally have its own alphabet, spellings of Ojibwe words in English can sometimes vary a lot, and most people use them interchangeably. Ojibwe comes from an Algonquian word meaning 'puckered,' probably because of the tribe's distinctive puckered style of shoes. The pronunciation is similar to o-jib-way, but many native speakers pronounce the first syllable very short or even drop it, which is why it sounded like "Chippewa" to some colonists.”

Anishinaabe

This term is not exclusive to Ojibwe. "Anishinaabe is an ethnic term, referring to the shared culture and related languages of the Algonquian tribes of the Great Lakes area. These tribes are not identical to each other, and they have their own individual identities and independent leadership. But they all share kinship ties and cultural traditions.” It means “original person.”

“Anishinaabe is the Ojibwe spelling of the word, usually pronounced similar to uh-NISH-ih-NAH-bay. In Potawatomi, the same word is spelled "Neshnabé" and is pronounced more like nesh-NAH-beah, rhyming with "yeah." Other common spellings of the name include Anishinabe, Anishnabe, Anishnaabe, Nishnaabe, Nishnabe, Nishnawbe, Anishnawbe, and Anicinabe. When the names end in -g or -k, those are plural forms (Anishinaabeg, Anishinabeg, Anishinabek, Anishinaabek, Anishnabek, Neshnabék, Anishnabeg, etc.) Anishinaabe people who are speaking in English or French will often use plural forms with -s instead (such as Anishinaabes or Anishinabes.)”

Anishinaabemowin

“Anishinaabemowin is the indigenous name used by the Anishinaabe peoples to refer to their languages. It literally means "original people's language." Since "Anishinaabe" is a general term used by several Algonquian speaking tribes of the Great Lakes and prairie regions, "Anishinaabemowin" (or one of its many spelling variants like Anishinabemowin, Anishnabemowin, Nishnaabemowin, etc.) can sometimes be used to refer to more than one distinct language, such as the Ojibwe, Algonquin, Ottawa, Oji-Cree, or Potawatomi languages. These languages are all related but are not identical-- the situation is similar to languages like Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Italian in Europe, all of which share many features yet still are not interchangeable.”

What term should be used?

This should not be taken as a blanket statement that can be applied to all individuals and scenarios, but in many cases Anishinabe is preferred, Ojibwe is accepted, and Chippewa is disliked, as it is a French mispronunciation of Ojibwe. However, you will still see Chippewa on official documents/written as part of names because of how well-known the term is.

Sources:

http://www.native-languages.org/definitions/anishinaabemowin.htm

http://www.bigorrin.org/chippewa_kids.htm

https://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plans/anishinabeojibwechippewa-culture-indian-nation

Simple Words and Phrases

Learn a few Ojibwe words and phrases!

Aaniin [ah-neen] = Hello

Miigwech [mee-gwetch] = Thank You

Click Here for a basic vocabulary list

Current Status of Language

Tragically, the last native speaker of Ojibwe living in Wisconsin passed away due to covid (though these numbers can be hard to define). There are about 25 people in the state that speak the language, but efforts such as Waadookodaading Ojibwe Language Immersion School are working to change this. UW-Madison and Eau Claire also offer Ojibwe language courses.

Learn more about Waadookodaading:

https://theways.org/story/waadookodaading.html

https://www.facebook.com/Waadookodaading-Ojibwe-Language-Immersion-School-176949672366355/

https://dpi.wi.gov/news/dpi-connected/ojibwe-language-immersion-school-ways

Wisconsin School Works To Keep Native American Languages Alive Around The World

The place where we help each other

Keeping the Ojibwe language alive: Michael Sullivan receives Ph.D. in linguistics

History

If not otherwise listed, credit to Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal [Patty Loew (2001)] and the Wisconsin Historical Society for the following information.

General Overview

Clan System

Ojibwe clans were patrilineal, meaning the clan a child belonged to depended on their father. You were not permitted to marry within your clan. There were seven original clans that each had a different function:

Crane and Loon — Leadership

Fish — Intellectuals and Mediators

Bear — Protectors (“Police,” Medicine, Healing)

Marten — Warriors

Deer — Poets

Birds — Spiritual

Image Credit: https://dp.la/item/594f837b1ca90e3d06f19c8e95537d77?q=ojibwe%20wisconsin&page=1

Migration to Wisconsin

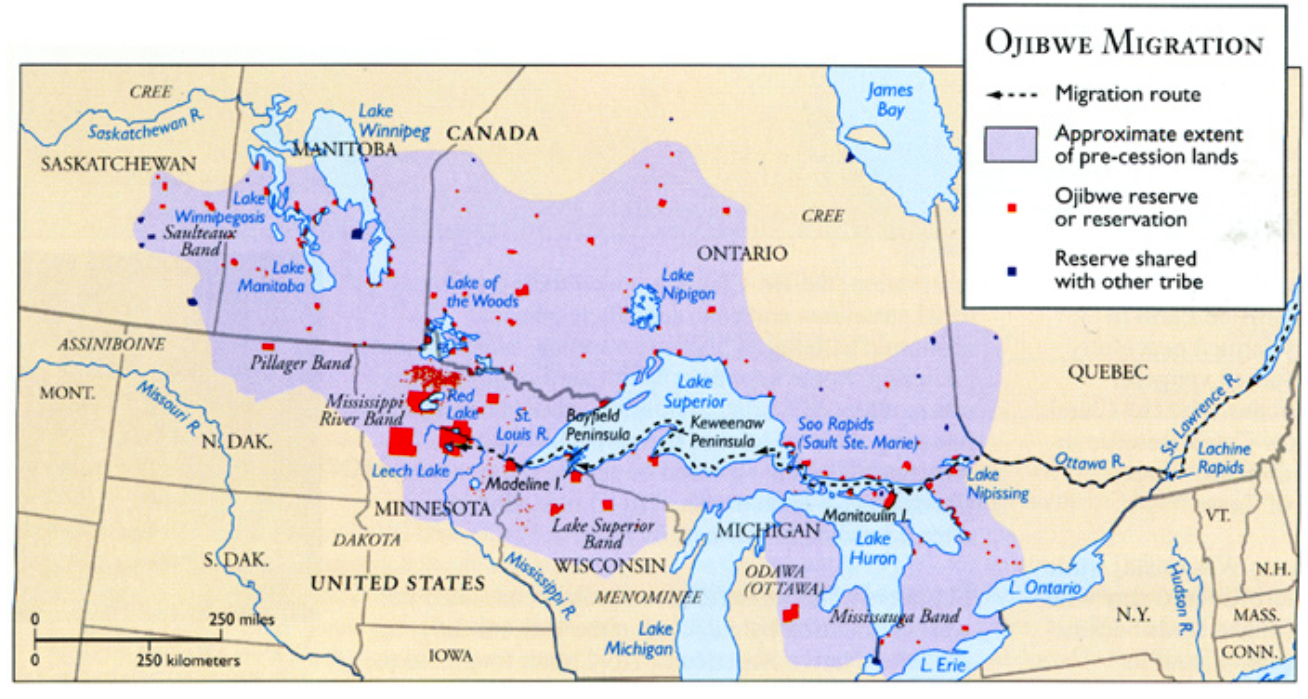

The Ojibwe were one of the “refugee” tribes that originally were living in the modern-day New York area near the Hudson Bay. Around 1500 they began moving westward.

Along the way, they stopped at what is known today as Madeline Island, named after the Christian name of a daughter one of the leaders took upon marrying Michael Cadotte. La Pointe became an economic and spiritual center.

They settled in the southern region of Lake Superior, prospering off the Manoomin wild rice they found there.

Image Credit: https://project.geo.msu.edu/geogmich/ojibwe.html

Migration Within Wisconsin

Due to environmental stress/lack of resources, religious divisions from missionary presence, and a growing population, they began to move south. This encroached on Ho-Chunk territory and led to conflict.

Image Credit: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM128692

Hunting

In earlier years, the Ojibwe were made up of smaller, more mobile bands. This is because the north had shorter growing seasons, which meant they depended more on hunting/trapping than agriculture. Due to this focus, they became better with rifles, but this led to more deadly conflicts. Wild rice was a diet staple.

Seasons dictated their lifestyle.

Spring — Fish and maple

Summer — Lots of fishing, a bit of hunting, women planting gardens and harvesting berries/nuts

Late Summer — Wild rice

Winter — Deer hunting and beaver trapping

Image Credit: https://www.thoughtco.com/ojibwe-people-4797430

Relationships with Europeans

They were generally known for being friendly with the French, benefiting greatly from trade, especially when it came to weaponry. They allied with the French to fight the British.

Image Credit: https://www.dibaajimowin.com/tawnkiyash/the-westward-expansion-of-the-ojibwe

Prairie Du Chien Treaty of 1825

This was a treaty signed between the United States and various tribes. It includes over 40 Ojibwe signatures, showing that they did not have one central leader. It created more official boundaries between tribes. It wasn’t necessarily clear to the tribes at the time, but this would make subsequent land seizures much easier for the US government.

Image Credit: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM3142

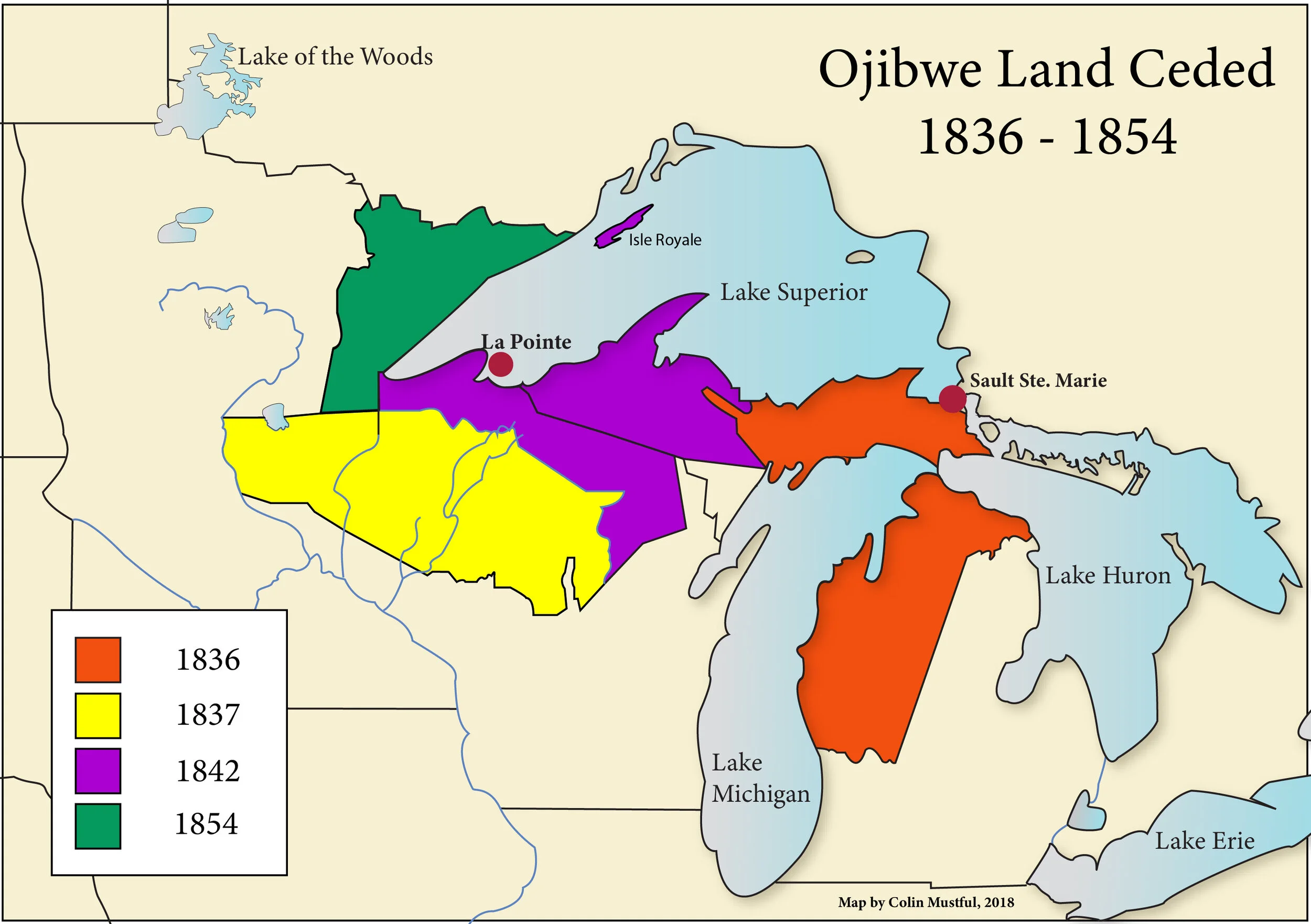

Land Cessions

In 1826, Ojibwe were brought to Fond Du Lac to basically scare them into submission, the US flaunting their weapons. Being decentralized and not having a very developed military put them at a clear disadvantage.

“In 1837, Ojibwe chiefs and government officials met near present-day St. Paul, resulting in the sale, or cession, of 13 million acres in east-central Minnesota and northern Wisconsin. The transaction was contingent on the Ojibwe retaining rights to hunt, fish, and gather on the newly ceded territory. […] An additional provision to the treaty required the United States to make annual payments called annuities to band members for 25 years. Annuity payments generally included cash, food, and everyday utility items. Five years later, Ojibwe headmen and government representatives agreed upon a 10-million-acre land cession that included portions of northern Wisconsin and Upper Michigan. The treaty opened the south shore of Lake Superior to lumberjacks, along with iron and copper miners. Similar to the previous 1837 arrangement, the 1842 Treaty guaranteed the Ojibwe's hunting, fishing and gathering rights and promised annuity distributions.”

“In 1850, a removal order was issued for the Ojibwe bands, but a delegation [that walked to Washington D.C.] was able to convince President Fillmore to rescind the removal order and begin the setup of permanent reservations. Treaty negotiations of 1854 established four reservations for the Ojibwe bands (Bad River, Lac Courte Oreilles, Lac Du Flambeau and Red Cliff), and again insisted on rights to hunt, fish, and gather on ceded lands.” They memorized the treaties to make sure they remained in compliance, but the US still abused their power and disregarded many of the provisions they had agreed to. The St. Croix and Mole Lake (Sokaogon) did not go to the 1854 negotiations, and thus remained landless for 80 years.

Source: http://www.glifwc.org/publications/pdf/SandyLake_Brochure.pdf

Image Credit: https://www.colinmustful.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/CededTerritory.jpg

Forced Assimilation

Forced assimilation has resulted in the loss of language, culture, and generational trauma that hurt the generations of the past, is hurting the people at present, and will hurt generations to come.

“The years following the creation of the Ojibwe reservations included many damaging policies of assimilation that affected the Ojibwe. The General Allotment Act in 1887 reduced the total Ojibwe land base by more than forty percent. The federal government divided land into 80 acre parcels for each tribal member, when land used to be owned communally, and sold the rest. Forced boarding school education, starting as early as 1856, required children to be taken away from their families and communities and placed in government schools.

School teachers and administrators strictly forbade the use of Ojibwe language, religion and culture. In these boarding schools, conditions were poor, corporal punishment was widespread, illness was spread and corruption was common among superintendents. There were industrial schools in Lac Du Flambeau, Hayward, or Tomah and parochial schools like St. Mary’s in Bad River, but some children were even sent to boarding schools in other states [such as Carlisle in Pennsylvania]. Children were stripped of their Ojibwe identities and given education in menial labor to enter domestic service, or become farm hands or laborers. Students were often forced to work in these types of jobs for exploitative wages over the summer instead of returning home [the outing system]. The boarding school era did untold damage to Native American children and communities in Wisconsin and throughout the nation.”

Image Credit: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM35888

Post-Boarding School Era

Forced assimilation has resulted in the loss of language, culture, and generational trauma that hurt the generations of the past, is hurting the people at present, and will hurt generations to come.

“The boarding school era and allotment officially ended with the passing of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, encouraged by Bureau of Indian Affairs commissioner John Collier. Ojibwe bands were able to reorganize their tribal government structures and apply for community development funds. Following the IRA, the “lost bands” of Ojibwe that did not receive land in the 1854 La Pointe Treaty, the St. Croix and Mole Lake Sokaogon bands, were able to establish reservations and tribal governments.”

Men played an important role in WW1 and WW2.

“The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, following World War I, was passed partially in recognition of the thousands of Indians who served in the armed forces across the nation. In addition to many other examples of honorable service, men from Wisconsin Ojibwe bands were “code talkers” in the Thirty-Second Infantry Division in the South Pacific, using the Ojibwe language to communicate.”

Post-WW2 was extremely challenging, Ojibwe being forced into cities and left without ways to find jobs. They maintained their tribal status, unlike the Menominee, but it was still a very difficult time.

The American Indian Movement, AIM, played an important role in the 1971 conflict between the Northern States Power Company and the La Courte Oreilles over rice beds.

In 1974, the Lac Courte Oreilles (and subsequently the other Ojibwe bands) raised a class-action lawsuit against the State of Wisconsin for violation of treaty rights, especially relating to fishing. They lost the first trial, but the decision was reversed in 1983.

Image Credit: https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM126965

An overview of treaty rights: http://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-110

Specific Bands

Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

This band is often abbreviated as LCO.

Name

Lac Courte Oreilles is a lake that translated from French means lake short ears. The Ojibwe term for the lake is Odaawaa-Zaaga'iganiing, meaning Ottawa Lake.

The French assigned this name after they encountered the Ojibwe people and believed that they were cutting their ears to make them shorter. This wasn’t true, but was perhaps influenced by other groups elongating their ears with heavy earrings, making these seem short in comparison.

Image Credit: https://www.travelwisconsin.com/article/fishing/best-places-to-fish-in-wisconsin-lac-courte-oreilles

Historical Overview

They first arrived in the modern-day Hayward area around 1745, eventually driving out the Sioux that had lived there prior. There are not many historical records prior to European contact.

Their reservation was established in 1854. Their land was encroached on by local natural resource and power companies throughout the years, some of which have been mentioned above.

“Beginning plans in 1912, and finally carrying them out in 1923, the Wisconsin-Minnesota Light & Power Company built a dam and flooded 5,600 acres of reservation land including rice beds, cemeteries, and an entire village. The tribe was unable to plant new rice beds, and the remains of hundreds of deceased Ojibwe were disturbed, despite promises by the W-MLP Company to avoid both of these results.”

Image Credit: https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/lac-courte-oreilles-band-of-lake-superior-chippewa-indians-of-wisconsin/

Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa Community College

This is the only Wisconsin Ojibwe band with its own college. It is featured in the Post-Secondary Programs tab.

It is located in Hayward, Wisconsin and along with Waadookodaading shows their strong commitment to education and language revitalization.

Image Credit: https://www.lco.edu/

At Present

The population currently sits around 7,000. They have a robust community/social services network, and are divided into several communities: Chief Lake, Little Round Lake, New Post, Northwoods Beach, and Reserve.

Image Description: Art by Jim Denomie, LCO artist

Image Credit: http://www.bockleygallery.com/artist_denomie/available/01.html

Lac du Flambeau Band

of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians

Name

“This Ojibwe nation is known for spearing fish at night by the light of birchbark torches. French fur traders who watched this ritual called the village Lac du Flambeau, or Lake of the Torches." The Ojibwe equivalent is Wasswagani-Sagaigan.

Image Credit: https://www.wxpr.org/post/strawberry-island-heart-lac-du-flambeau#stream/0

Historical Overview

Like LCO, the tribe also settled in Wisconsin around 1745.

Fish was a diet and economic staple. “The tribe was loyal to the American colonies, never taking sides with the British or French and fought with the Union forces in the Civil War.” The US government created a boarding school on the reservation in 1895, which has had devastating emotional, economic, and cultural impacts on the community. Lumber and fur played a big role, especially early on, but were known for unethical practices.

Image Credit: https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/lac-du-flambeau-band-of-lake-superior-chippewa-indians/

At Present

The population currently sits around 3,500. They operate the Lake of the Torches Casino, in addition to hosting several other industries.

While they do not have any language schools, they operate a daycare, in addition to other community services, and welcome local language and culture.

Image Credit: https://lakeofthetorches.com/

Red Cliff Band

of Lake Superior Chippewa

Historical Overview

The Red Cliff are the people who stayed near Madeline Island post-mid-1700s Ojibwe diaspora. Red Cliff is located in the northern tip of Wisconsin.

“…Red Cliff was originally part of the LaPointe Band, the primary village of the Great Buffalo, Head Chief of the Anishinaabe. The Great Buffalo is a historical tribal leader, most widely known for his role as peacemaker in the formation of the Treaty of 1854…”

Religion proved to be divisive, an official split happening in 1854, the christianized Ojibwe under Chief Buffalo going to live near the Red Cliffs of Buffalo Bay and the traditional Ojibwe becoming Bad River. The two groups stayed on good terms.

Fishing and logging were central to their economy, but due to unsustainable logging practices, they quickly exhausted that resource. Before, and especially after, many of them were working for outside employers, competing against bigger companies and industries proving difficult. They were especially hard-hit by the Great Depression.

Image Credit: https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/red-cliff-band-of-lake-superior-chippewa-indians/

At Present

The population is currently around 5,000. Gaming (Legendary Waters Resort and Casino) helps support their economy and social services. “In 2012, the band created Frog Bay Tribal National Park, the first tribal national park in the U.S.” They also operate a fish hatchery. Language revitalization is part of their Head Start program.

Image Credit: https://wisconsinfirstnations.org/frog-bay-tribal-national-park/

Tribal Website: https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/

Additional Sources:

http://www.thenetworkwi.com/red-cliff

https://dpi.wi.gov/amind/tribalnationswi/redcliff

https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/red-cliff-band-of-lake-superior-chippewa-indians/

https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/community/heritage_and_culture/miskwaabekong_history.php

Bad River Band

of Lake Superior Chippewa

Historical Overview

The Bad River Band was the other half of the Ojibwe split at Madeline Island, considered the pagan faction of the two. It is the last of the four 1854 treaty-created reservations.

“In 1856 a small Christian boarding school was started to educate Ojibwe boys and girls, and in 1883 a larger Catholic school, St. Mary’s was constructed. In the early 1900s, Stearns Lumber Company was a large company that held a monopoly in Bad River, controlling all major businesses and conspiring with the Indian Agent to extort tribal members and illegally gain land for logging.”

“The original religious society is known as Midewiwin or Grand Medicine Lodge.”

Image Credit: https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/bad-river-band-of-the-lake-superior-tribe-of-chippewa-indians/

At Present

The population currently sits at around 7,000. It is the largest employer in Ashland County and the largest Ojibwe reservation in the state with the vast majority of their land undeveloped. “Odanah, the Ojibwe word for town, is the main village and the seat of government for the tribe.” They have a casino (Bad River Lodge and Casino) and a fish hatchery. The Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) is headquartered on the reservation.

Image Credit: https://glifwc.org/blank.php

Sokaogon Chippewa Community

Mole Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa

Historical Overview

“As the Ojibwe migrated to other parts of the Great Lakes region, a group known as the “Post Lake Band” under the leadership of Ki-chi-waw-be-sha-shi settled on land near current-day Rhinelander.”

“Sokaogon means "Post in the Lake" people, because of the spiritual significance of a post, possibly the remains of a petrified tree, that stood in nearby Post Lake.”

The Battle of Mole Lake in 1806 between the Sioux and the Ojibwe over rice bed control resulted in hundreds of casualties.

“The nation was known as the “Lost Band” when the maps showing where their reservation would be were lost in the mid 1800s. Land was finally purchased for the tribe’s reservation in 1934.” In the interim, they suffered from extreme poverty. Chief Ackley was instrumental in this process.

Image Credit: https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/sokaogon-chippewa-community/

At Present

The population currently is quite small, just over 1,000.

“The introduction of bingo and casinos [Mole Lake Casino and Lodge] drastically altered unemployment on the reservation. Rates fell from 80% to 10% within a couple of years.”

Image Credit: https://molelakecasino.com/

Tribal Website: http://sokaogonchippewa.com/

Additional Sources:

http://sokaogonchippewa.com/about-us/history/

https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/sokaogon-chippewa-community/

https://dpi.wi.gov/amind/tribalnationswi/sokaogon

https://wisconsinfirstnations.org/current-tribal-lands-map-native-nations-facts/

St. Croix Chippewa

Indians of Wisconsin

Historical Overview

St. Croix was the other lost band of the Ojibwe, also not being recognized for 80 years till 1934.

There was intermarriage with a lot of different groups, so it wasn’t always clear who was part of the St. Croix band.

Image Credit: https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/sokaogon-chippewa-community/

At Present

The population of this band hovers around 1,000 today. Similar to others, they rely on a casino (St. Croix Casino at Turtle Lake) to support their social services.

“The Annual St. Croix Wild Rice Pow-wow has been in existence for more than 20 years. The three-day celebration takes place at the Tribal Center in Hertel in late August, and hosts drums and singers from all over North America.”

“The five major communities are Sand Lake, Danbury, Round Lake, Maple Plain, and Gaslyn.”

Tribal Website: http://www.stcciw.com/ (however appears to be non-functional)

Additional Sources:

https://www.glitc.org/tribes-served/saint-croix-chippewa-indians-of-wisconsin/

https://dpi.wi.gov/amind/tribalnationswi/saintcroix

https://wisconsinfirstnations.org/current-tribal-lands-map-native-nations-facts/